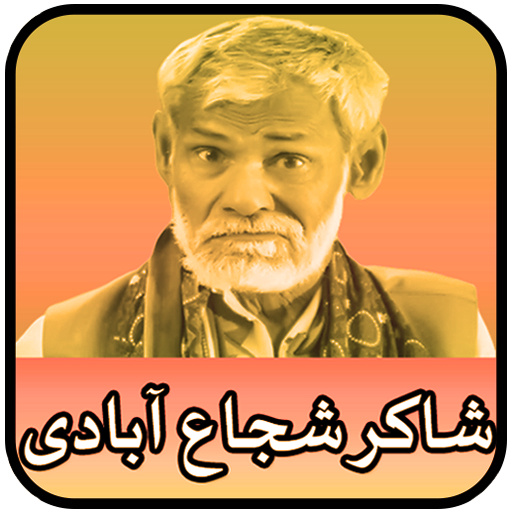

Shakir Shujabadi is a prominent Saraiki-language poet in Shujabad, a small city near Multan, Pakistan. In 2007, he received his first presidential award. In 2017, he received his second presidential award. His first proper Mushaira was held in 1986. He cannot speak properly due to a physical disability.

Achievements

He is a Saraiki/Punjabi poet, who started to recite his thoughts at the local darbar. He had achieved prominence in Saraiki culture by the early 90s. His first proper Mushaira was held in 1986. He headlined the All-Pakistan Mushaira held in 1991. The last Mushaira before his childhood condition got worse was held in 1994, but he still recited.

His poetry is laced with beautiful prose, which offers riddles regarding the world and society. He discusses themes of honesty, poverty, inequality, and underdevelopment related to the region. His ability to surpass linguistic barriers and appeal to non-Seraiki speakers is very powerful.

Among his best-known verses are ‘Tu Mehnat Kar, Tay Mehnat da Silla Jaane Khuda Jaane’ (Just work hard and reward for that hard work, only God knows what you will get) and ‘Tu dewa bal kay rakh shakir, Hawa jaane khuda jany’ (Light the lamp, and let the winds decide or fate decide).

Shakir was forced to work as a fruit seller. He was entrenched in the vicious cycle of making ends meet in Bhawalpur. Poetry was still not in the picture. He then moved to Karachi, where he worked at two jobs both as a fruit seller and chowkidar but was later forced out of the workforce. He tried to spend his life working, but his health and age didn’t allow it. Poetry came to him when he had nothing.

There are several popular lines, such as Tu Mehnat Kar, Tay Mehnat da Silla Jaane Khuda Jaane (Just work hard and reward for that hard work, only God knows what you will get.) or Tu dewa bal kay rak ja, hawa jaane khuda jaane (Light the lamp, and let the winds decide or fate decide).

When it comes to Seraiki poetry, Shakir Shuja Abadi is one of the biggest names. Almost every columnist in Seraiki has written extensively on his work. He is in dire shape, says Nazar Farid Bodla, a student and an apprentice of sorts, who is now officially assigned by Shakir to recite his poetry.

According to Bodla, it has been two years since the Punjab government stopped providing Shakir a stipend and he has not been able to work either. Bodla tells that Shakir’s house is small, and the family has no lands or supplementary income. Shakir has been dependent on hand-outs from an MNA, or if a poetry recital takes place, he writes down poems for Bodla to recite.

My father is not well, tells Waleed, the younger son of Shakir. Waleed has returned home to be with his father, who in Seraiki folk culture is a literary figure. Most regional languages are overshadowed by the prominence of Urdu or English, and Seraiki is no exception. Due to this, we forget the hidden geniuses that are yet to be discovered in the heart of our country.

Waleed says only a few friends and fans have visited regularly since his father has been bed-ridden. Shakir’s poetry is still published regularly in a newspaper, whenever Shakir pens a thought. Most of his life’s work has been built out of the experience and the process of life itself.

It is said that his poetry came from a dark place of struggle and uncertainty, because of a stroke that he suffered as a child. He managed to attend a local government school, from where Shakir later dropped out after the death of his grandmother. It is unfortunate to see talent such as that of Shakir being wasted due to sheer indifference.